About Te Tauranga

With Brian Morris

In the past wetlands extended to this point. Te Tauranga was on a slope just above the waterline.

During the 1600s, Pukekaihau was a thriving pā (settlement). It was the main pā for the hāpu (kin groups) of this area. They would go out and gather food from surrounding waterways and forests, then move back up the hill, behind the fortifications, during times of danger.

Te Tauranga means 'landing place'. People travelling from mahinga kai (food gathering places) or other pā moored their waka (canoes) here when they arrived. Kiripara Stream, which connected Lake Whatumā with the Tukituki River, ran nearby and enabled waka travel to and from the pā.

In the past wetlands extended to this point. Te Tauranga was on a slope just above the waterline.

Te Tauranga was an important arrival point for the people who lived at Pukekaihau Pā and visiting guests.

To navigate the wetlands, the tīpuna (ancestors) built specialised waka tīwai (dugout canoes). You can see a surviving example at the Central Hawke’s Bay Settlers Museum.

Pukekaihau Pā was a pā tūwatawata (fortified settlement). Rising from a hilltop surrounded by seasonal wetlands, Pukekaihau Pā was a secure place of refuge that could be defended easily, like a castle. Palisade fences of heavy, three-metre-high posts provided the physical defences. They were arranged like a maze to confound would-be attackers.

Pā tūwatawata were carefully designed to provide layers of security during times of danger.

The pūhara (watchtower) offered a commanding view over the landscape and its resources. Sentries were stationed here to alert the pā inhabitants to any threats.

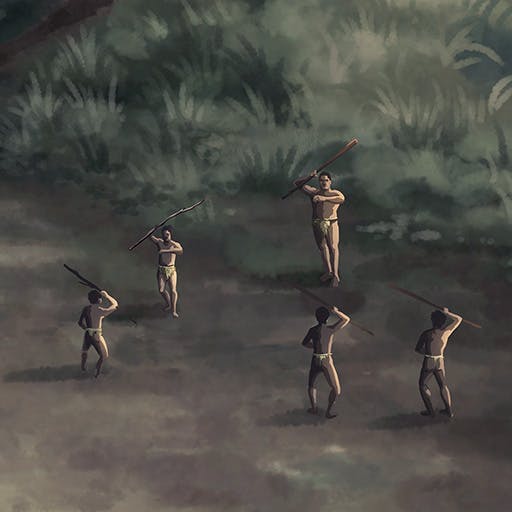

The tīpuna (ancestors) needed knowledge of warfare and mau rākau (Māori weaponry), to protect their hapū. They learnt this from a young age. It was part of the teachings of whare wānanga (houses of learning), as were other forms of essential knowledge – like fishing, weaving and horticulture.

The tīpuna (ancestors) lived in whare (houses) arrayed along the ridge. At the tihi (summit) stood the house of the rangatira (chief). A pure, unfailing komanawa (spring) flowed from the highest point.

The kōmanawa (spring) was a key reason the tīpuna decided to build on this site. The pure water was ideal not only for drinking, but for conducting rituals related to birthing, baptism, cleansing and purification.

The whare (houses) were built into the earth and sides of the hill to retain warmth. They were mostly used for sleeping.

Pukekaihau Pā bustled with groups engaged in kai (food) production and industry. The tīpuna (ancestors) gathered kai from nearby waterbodies and forests. Diverse kai brought to this pā at different times of year included harakeke (New Zealand flax), aruhe (fern root), berries, pollen, kererū and other birds, tuna (eels), fish, kākahi (freshwater mussels) and kiore (Polynesian rats).

Kai was stored in pātaka: storehouses raised on posts, to keep it safe. Pātaka of varying sizes served different whānau (family) groups. Chiefs had large, ornately carved pātaka, signalling their mana (power and authority) and allowing them to provide for their own people as well as any guests who visited the pā.

Hāngī (earth ovens) could steam large quantities of kai underground: eels wrapped in flax, kākahi (freshwater mussels), kūmara, taro, and fern roots.

The tīpuna held sophisticated knowledge about gathering and preparing food from the water: tuna (eels), assorted fish, kōura (freshwater crayfish), kākahi, and puha (watercress).

Birds – like kererū, kākā and tūī – were an important food source. The tīpuna created a range of snares and spears to catch birds in the forests.

Kiore (Polynesian rats) were a valued source of protein.

The tīpuna maintained pākihi and karinga aruhe (fern root cultivations). They dried the fern roots, then later processed them for eating by soaking them in water, roasting them, and pounding them to soften them.